Biological Warfare Development

In addition to its chemical warfare development, the Imperial Japanese Army sponsored a large-scale, systematic program to develop and experiment with biological warfare. Japanese scientists were doing research for this program in facilities established throughout Manchuria from the beginning of its occupation in 1931-1932 until Japan's surrender in 1945. The biological warfare programs were spearheaded by Japanese microbiologist and lieutenant general ISHII Shiro, who between 1928 and 1930 spent time in the West studying the effects of chemical and biological warfare. Shortly after his return to Japan, ISHII toured newly occupied Manchuria and saw an opportunity to use the area for further research and development. With funding from the Japanese government, ISHII established the biological warfare research facility code-named 'Unit Togo' in Beiyinhe, outside of Harbin in 1932.

Pingfang Complex

In 1934, a small number of prisoners escaped Unit Togo and spread word that humans were being used as test subjects at the facility. To maintain secrecy, ISHII decided to move operations to the more secluded location, which led to the establishment of the Pingfang complex in 1936 in Pingfang, 20 kilometers south of Harbin. The massive complex was built and operated by thousands of forced Chinese laborers, and could accommodate up to 3,000 Japanese staff members. Pingfang became the headquarters of the infamous Unit 731, the Imperial Japanese Army's largest biological and chemical warfare unit in occupied China. Other smaller facilities were established throughout China in places like Changchun, Nanjing, and Guangzhou, but nowhere came close to replicating the proportions of the Pingfang complex.

Biological Warfare Agents

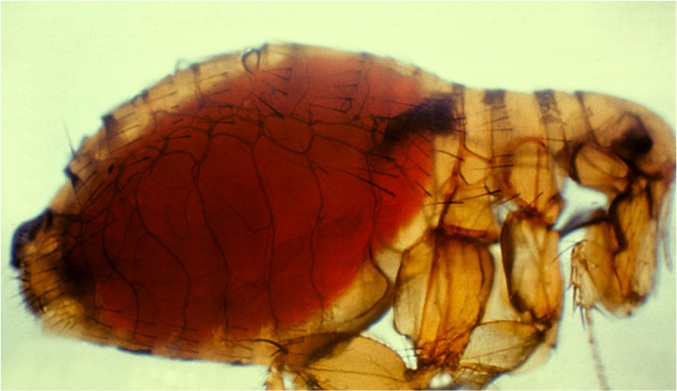

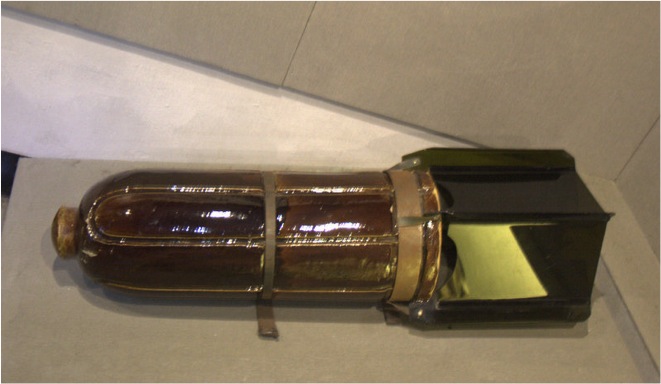

Many pathogens were tested as warfare agents, including the causative agents of plague, cholera, typhus, paratyphus, anthrax, gangrene, tetanus, and gas gangrene. At Pingfang and elsewhere, scientists used culture boxes to produce bacteria. It is thought that over a thousand culture boxes were inoculated and harvested daily at Pingfang alone. The researchers tested their pathogens on human subjects, and experimented with ways to use animals and insects as transporters of the biological weapons. Perhaps the most successful method included the use of the Oriental Rat Flea as a carrier of the bubonic plague. They were able to produce the infected fleas at a rate of about 150 million per three-month cycle. Around 30,000 infected fleas would be encased in a porcelain bomb, called an Uji bomb, and dropped from planes. They also infected clothing, blankets, other animals, and even kids' candy as a way to spread biological agents.

Use of Biological Weapons

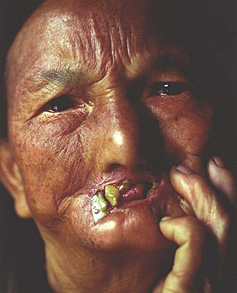

Starting in 1939, the Japanese military began using biological warfare in attacks. One of the first major incidences was a plague attack on Quzhou, Zhejiang Province in 1940, which caused an epidemic that killed over 5,000 people between 1940 and 1948. In 1941, there was a plague attack on Changde, Hunan Province, the effects of which have been well documented. Another major incidence occurred in 1942, after Tokyo was first attacked by American bomber plans. Japanese retaliated by attacking villages in the Zhejiang province-where the villagers had aided the American airmen-with biological agents. Some of the survivors from these attacks were left with festering ulcers on their legs that never healed. Those survivors now live in what are known as 'rotten leg villages' throughout the Zhejiang province.

At the end of the war, the Imperial Japanese Army destroyed its biological warfare facilities, but the nightmare did not end there. As a final attack, and in full awareness of the long-term effects that would occur, the Japanese released the plague-infected animals from the facilities. Resulting plague outbreaks killed at least another 30,000 innocent civilians between 1946 and 1948.